July 24, 2017

Studio Visit with Karl Fritsch in New Zealand

July 24, 2017

Images and content here is connected to Critical Craft Forum iTunes Podcast, Episode 3.

Not on iTunes? Connect here.

Karl Fritsch defies any idea that production work is repetitive. Known internationally for working through rings, the installation of his work is as singular as each piece. This episode drops you into a conversation between Karl Fritsch and Namita Gupta Wiggers in the artist’s studio in Wellington, New Zealand from the summer of 2016. We talk about collaboration, process, materials, and the ways in which Fritsch challenges any sense of production – whether of a ring or an exhibition – as repetitive or repeatable.

These snapshots, taken during my visit to New Zealand at the invitation of Dr. Damian Skinner and Creative New Zealand, give a context to the conversation in the iTunes podcast.

HUGE thanks to Karl for taking the time to speak with me, show me around his studio, share some books, and for a delightful lunch.

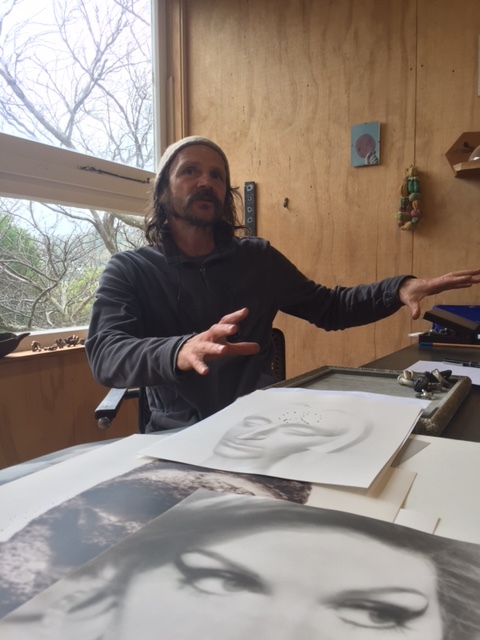

Karl Fritsch in his Wellington, NZ studio.

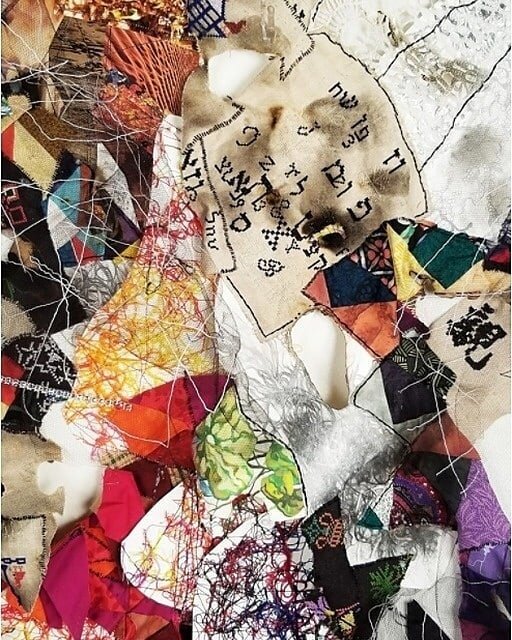

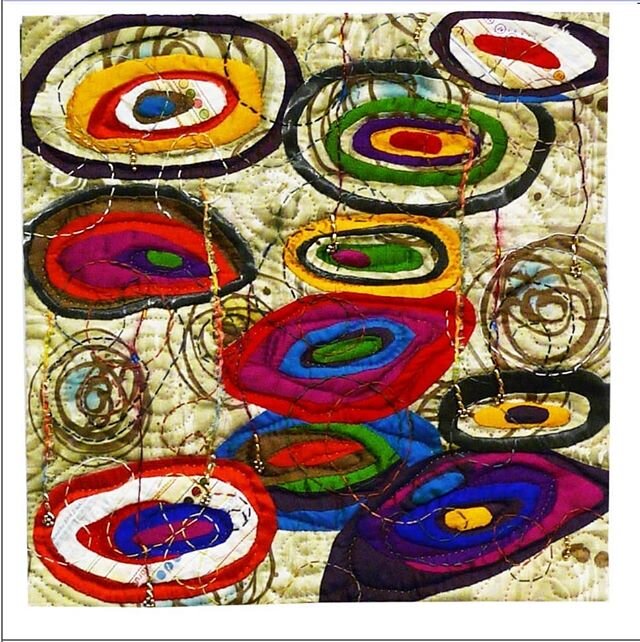

Work in progress at this table includes an ongoing collaboration with Gavin Hipkins. Their collaboration has become a consistent part of their work. As discussed in the podcast, on some occasions Karl responds immediately to the photograph with stone setting -- while other images are engaged over time, with a combination of stone setting, sculptural or physical responses to the paper itself. To describe Karl's work as collaborative is an understatement - he thrives on creative and critical interaction -- and his ongoing partnerships with Warwick Freeman are in part what piqued my curiosity to talk with him. Our conversation came just after an international tour of Wunderrūma: New Zealand Jewellery, in which each iteration involved a site responsive installation. This works directly against the tendency in museums of various sizes to treat touring exhibitions as a package, a container of objects to be installed with adjustments in each hosting venue. The tour of this project created a new experience with each site, leaving historians to sort through reviews by Finn McMahon-Jones in The Journal of Modern Craft and Peter Deckers' article on Art Jewelry Forum, by Warwick Freeman in Garland and at The Dowse Art Museum (the organizers of the project) to understand the full scope of this morphing exhibition.

This fluidity to respond, shift, and adjust to spaces manifested in a different form in Wellington at the same time as our studio visit. Here, Karl Fritsch's collaborations could be found in three art spaces -- the commercial gallery run by Hamish McKay, a contemporary art space run by the city of wellington, and at the Te Papa, a national museum dedicated to representing a bicultural community through its exhibitions, scholarship, and programs. Even in Europe, where contemporary art jewelry is visible in public collection displays in museums -- in Germany and the Netherlands, for example -- the kind of seamless movement between contemporary forms was refreshingly unique, provocative, and stimulating in Wellington.

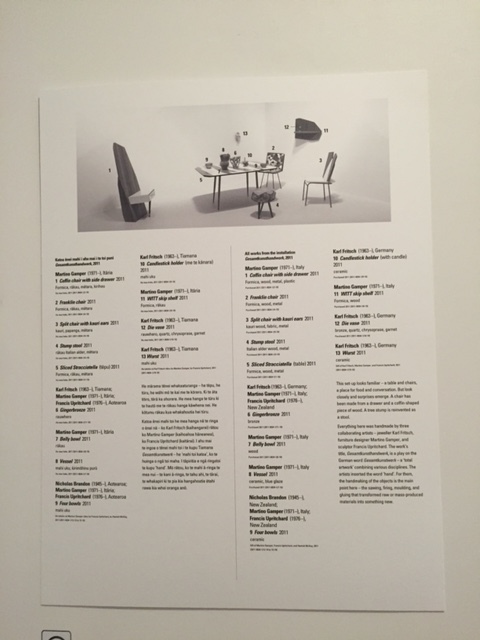

Images from Hamish McKay Gallery, where Francis Upritchard curated The Neighbor, a group exhibition including works by Karl Fritsch, Martino Gamper, Ronnie van Hout, Diena Georgetti and Laurie Steer. Upritchard's exhibition Jealous Saboteurs was on view at City Gallery; see an exhibition review by Sian van Dyk in Journal of Modern Craft.

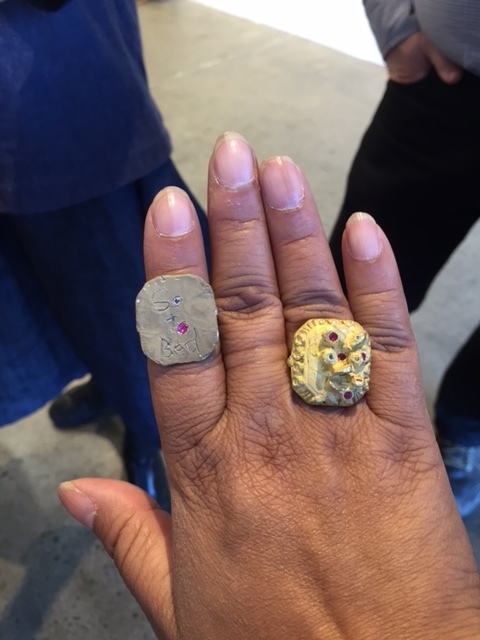

Special thanks to Hamish McKay for opening early for us. Rings by Karl Fritsch "modelled" by Sian van Dyk of The Dowse Art Museum and Namita Gupta Wiggers.

Please click to advance images.Slide Show of Karl Fritsch's studio, Wellington, New Zealand, July 2016.

Building a national collection in New Zealand means including contemporary art jewelry as well as other forms of craft and craft-based work, as evidenced by Collecting Contemporary at Te Papa. For more information about this exhibition and collection building, see behind the scenes blog posts here.

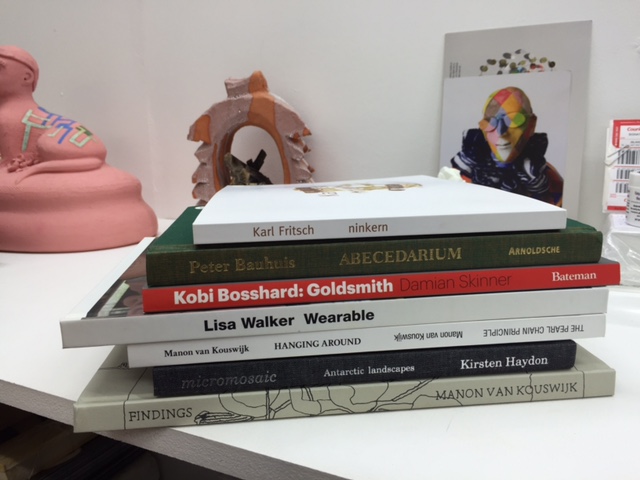

Caroline Billings of The National, a jewelry gallery in Christchurch, generously walked me through every artist's work in her gallery -- which included the opportunity to try on more rings by Karl Fritsch. This stack of publications represents only a small portion of the scholarship dedicated to contemporary art jewelry in New Zealand -- and the deep commitment to academic research and writing I witnessed everywhere -- from museums to galleries of all sizes and focus. For a sense of the breadth of writing and publications -- each as unique as his exhibitions see this link to Robert Baines The Baby Brick and other publications focused on Karl Fritsch's work on Klimt02. Much like his rings and exhibitions, no publication is like the other, and while the forms pivot on the archetypal ring, Karl Fritsch offers a fresh lens into the creative possibilities of repetition, production, and collaboration.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

New for CAA in 2018!

Critical Craft Forum will present a full day, on-site super session at the 2018 College Art Association Conference in LA curated by Shannon Stratton,Namita Gupta Wiggers and Marilyn Zapf.

Proposal deadline: April 17

The Critical Craft Sessions will be held Saturday, February 24; four sessions in total (90 minutes each).

We invite and encourage you to submit panel and paper proposals to College Art Association. To be considered specifically for the Critical Craft super session please list: Critical Craft Sessions on your submissions. All other craft-focused proposals will be considered alongside general CAA submissions.

See CAA link for instructions and details on how to apply: http://www.collegeart. org/news/2017/02/27/ conference-submissions-for- caa-2018/

NOTE: CAA membership is required to submit a proposal.

All panelists/presenters will need to register and pay for conference attendance (see CAA for information on full-day or reduced rates). Online registration for CAA 2018 will begin on October 2, 2017.

Questions? email criticalcraftforum@ gmail.com

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

February 14, 2017

Portland, OR to NYC

College Art Association is underway!

The 8th Critical Craft Forum: Gender and Jewelry takes place at 1030 am - 1200 pm on Thursday, February 16.

Location:Sutton Parlor South, 2nd Floor

Chairs: Namita Gupta Wiggers, Critical Craft Forum; Benjamin Lignel, Independent Curator and Writer

Meredith P. Nelson, Bard Graduate Center

Emily K. Rebmann

Julia Heineccius, The Evergreen State College

James Tigger! Ferguson, Fashion Institute of Technology

renée c. hoogland, Wayne State University

Discussant: Jenni Sorkin, University of California, Santa Barbara

Session Abstract:

Despite the connection between jewelry and the body, significant critical analysis of the relationship between gender and adornment – particularly of contemporary art jewelry – is nascent at best. This panel explores connections between this subject and forms of adornment, ornament, and art jewelry. Panelists will each present their research in brief, focused 8 minute talks, to be followed by a respondent and workshop/discussion amongst panelists and attendees.

The goals: to identify and work collaboratively with researchers and artists to explore the relationship between gender and jewelry; to work collectively prior to the panel to build a core group with shared interests via ww.criticalcraftforum; to publicly share individual research investigations; and to use the broader collective group of CAA attendees to further questions, thinking and concerns to expand critical frameworks for further study. Collective project work for this session with panelists and panel attendees will be acknowledged and explored in a forthcoming publication – the first to critically examine gender and art jewelry – currently being researched by Lignel and Wiggers.

Panelists will each present their research in brief, focused 8 minute talks, to be followed by a respondent and workshop/discussion amongst panelists and attendees.

Papers, Speaker Info, and Paper Abstracts:

Speaker 1: Meredith P. Nelson, Bard Graduate Center

The gold body chain (catena) is a Roman jewelry form that is represented by a small corpus of pieces, uncovered primarily in excavations of the Vesuvian region, and dating to the 1st century A.D. Representations of catenae in contemporary visual media indicate that the body chain held distinctly erotic connotations, as it appears to have been worn only by women, over their bare torsos. Furthermore, the chains are found primarily in images of Venus and mortal women engaged in explicit sexual acts. Because of these illustrations, it appears the catena functioned in Roman contexts as an assertive, visual sign of female sexuality. The intersection of material remains and visual representation elicit deeper questions about the role of catenae in advertising female sexual autonomy, the status of the women who wore them, and the kinds of social environments in which such demonstrations were considered appropriate.

Speaker 2: Emily K. Rebmann

Historically, men’s jewelry has been subject to regulations that have not been applied to jewelry worn by women. These rules changed over time as well as in relation to event type and time of day, and can best be summarized as an unfaltering emphasis on “correctness” of style. The guidelines functioned as a “dress code” of sorts that established a “uniform” that could allow men to transcend the boundaries of class – if executed correctly. Though it is not possible to ascertain the precise number of men who followed this advice, the sheer magnitude of advertisements and articles that played off men’s social anxieties and the popularity of "correct" jewelry during the period lead to the following question: how, if at all, has nineteenth- and twentieth-century prescriptive literature impacted the jewelry worn by men in contemporary society?

Emily Rebmann obtained her B.A. from the University of Cincinnati's College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning, and her M.A. from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware. She first began researching jewelry and gender as part of her Master's thesis, entitled: "'Jewelry for Gentlemen': Krementz & Company's Men's Rolled Gold Plate." After completing her M.A., Emily managed and catalogued a selection of Krementz & Company archival documents and photographs, coordinating their donation to the Newark Museum in 2015. Most recently, she worked as an Engagement Officer for the Cleveland Museum of Art. Now, Emily is excited to take on her next role as the Site Historian for the Ohio History Connection.

Speaker 3: Julia Heineccius, The Evergreen State College

Jewelry everywhere and nowhere.

• How is jewelry used in the photographic description of bodies?

• When does jewelry no longer describe the body wearing it?

• What is the effect of opting-out of adornment?

In the images made by Annie Leibovitz of Caitlyn Jenner for Vanity Fair, jewelry is everywhere and nowhere. On the cover, there is no jewelry: just the hair vamped and flesh bodysuited in satin. In one of the interior article shots, the jewelry is negligible, especially when contrasted with the giant Olympic gold metal left on the table. The placement and scale of jewelry in these portraits authenticate gender (and wealth) and allow the lack of jewelry to be as descriptive as the presence of it.

Speaker 4: James Tigger! Ferguson

I have a sassy story to share about a sissy-gendered teen struggling to breathe in the Midwest who inherited the "Dead Grandma Collection" of garish costume jewelry, and how it helped to open a door he had been kicking against for as long as he could remember. It takes me an hour just to write a postcard. This story takes many, many postcards. My art moves very quickly onstage but takes a lifetime of preparation. New York’s leading boylesque performer since 1997, Actor/Dancer/Stripper/Performance Artist James Tigger! Ferguson has been stripping and grinding since 1988.

James Tigger! Ferguson - "The Godfather of Neo-Boylesque" is an actor/dancer/stripper/librarian who has performed in NYC since 1988 & around the world since 1993. A pioneer in the 1990s burlesque renaissance who won the 1st-ever "King of Boylesque/Mr. Exotic World" title at Burlesque Hall of Fame in Las Vegas 2006. Won several Golden Pastie Awards, including "Most Likely to Get Shut Down by the Law" & "Most Unpredictable Performer." His act was banned at Rome's Gay Village. He has acted in Shakespeare, Apollinaire, Euripides, Wedekind, Horváth, Williams & numerous original works with Taylor Mac, Julie Atlas Muz, Talking Band, Target Margin Theater (where he is an Associated Artist) & other geniuses.

Press: "a fantastically watchable naughty satyr" by The Scotsman, "disturbing, funny and oddly riveting all at once" by Vancouver Sun, "the Boylesque King...a heart-pounding climax" by LA Weekly, "an irresistible performance… with Tigger! at the helm, you can’t help but have a blast." by EdFestMag, "hysterical and acrobatic" and "wickedly arch" by The New York Times, "delightful... simultaneously hilarious and titillating" by TheaterMania, "a brilliant satirist" by examiner.com, "the Taboo-Defying Dynamo" by NEXT Magazine.

Tigger-James Ferguson | Facebook

Speaker 5: renée c. hoogland, Wayne State University

The thrust of my argument will be that becoming non-heterosexual, both epistemologically and ontologically, is, first of all, a radically historical process, but also an undeniably materially embodied/embedded phenomenon within an ever-emergent system of linkages with material objects and practices. That this, at least theoretically, equally holds true for dominant or straight modulations of becoming does nothing to detract from the fact that it is in its material practices, manifestations, and effects that the latter, heterosexuality, appears, and thus obtains as a form of natural or transcendent being, while the former, queer becoming, primarily consists in activity, in what Alfred North Whitehead calls “actual” or “living occasions,” orwhat Deleuze and Guattari describe as intensive “events” within complex matrices of materiality.

renée c. hoogland is Professor of English at Wayne State University in Detroit, where she teaches literature and culture after 1870, critical theory, cultural studies, and visual culture. She has published widely in American and British literature, film, visual culture, and critical theory. Her most recent book is A Violent Embrace: Art and Aesthetics after Representation (UPNE, 2014). hoogland regularly publishes art reviews, catalogue copy, and other short pieces in art magazines. She is also the editor of Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts and senior editor in chief of Macmillan Interdisciplinary Handbooks: Gender.

WSU Faculty profile: https://clasprofiles.wayne.edu/profile/ec0769

Discussant: Jenni Sorkin

Jenni Sorkin is Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art History at University of California, Santa Barbara. She writes on the intersection between gender, craft, material culture, and contemporary art.

Website: http://www.arthistory.ucsb.edu/people/jenni-sorkin

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

November 13, 2016

Portland, OR

I've been on the road since October 7 with the exception of one week at the end of October, From Tulsa to Boston to Deer Isle to Omaha to Savannah to Portland to San Francisco and the Bay Area, conversations pivoted on the question of improving representation of the breadth of the USA in all aspects of organizational work -- from programs to board, content to attendees.

Now that the election results of the past week have shifted this conversation from timely to urgent, I am compelled to share the introduction I wrote to precede Sonya Clark's Keynote on Day 3 of the American Craft Council Conference PresentTense, held in Omaha NE this past October. Her work takes on new importance today - and into the future. I do not yet know how to write about the election itself, and this is the best I can offer at the moment.

Namita Gupta Wiggers: Introduction of Sonya Clark at American Craft Council Conference

PresentTense Conference, American Craft Council

OMAHA, NE

October 15, 2016

When asked to introduce my friend and colleague Sonya Clark, I immediately thought fondly of stories I’ve heard of another American Craft Council Conference.

In 1957, a young Ken Shores skipped his graduation ceremony at University of Oregon and deferred the start date of a job waiting for him in Portland, Oregon at Oregon Ceramic Studio – later Museum of Contemporary Craft – to head to the first ACC Conference at Asilomar.

It was there that Ken met Toshiko Takaezu. It was the start of a lifelong friendship that began in a community dedicated to craft.

Fast-forward to 2006 and the first ACC Conference in decades. Several generations gathered again to discuss the state of the field. It was there that many of my cherished friendships began, an especially my friendship with Sonya Clark. Where Ken and Toshiko connected annually for many years to conduct ceramic workshops – Sonya and I have spent the Thursdays preceding ACC Board meetings with afternoons at the Walker Art Center. She is the best of museum companions – especially when we get rambunctious and were told to quiet down at the Museum of Arts and Design in NYC.

I could introduce Sonya Clark through her educational credentials – she holds an undergraduate and more recently honorary doctorate from Amherst College, a BFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and an MFA at Cranbrook Academy of Art – but these academic institutions are hardly the beginning of her connection with craft. Sonya Clark reminds us that craft begins at home, where learning to make and listening to stories become the catalysts of a life’s work.

I could introduce Sonya Clark by listing her residencies in Italy, China, the US and more. It’s an impressive list – but doesn’t begin to communicate how Sonya employs these opportunities to create her work. The list tells where she’s been – but doesn’t reveal how she works outward and builds communities around the globe through connections with artists with whom she works, talks, and relaxes in these productive environments. Sonya Clark’s work and life remind us of how the world and the individual are inextricably intertwined.

I could list any of the over 300 museums and galleries across the globe in which you may have seen her work – or awards such as a United States Artist Fellowship, the Art Prize, and most recently, the 2016 Anonymous Was a Woman.

But I think, instead, that I want to talk about what Sonya Clark makes.

She reminds us of the strength and metaphoric power in the everyday.

She moves in the commonplace, transforming objects to things or materials for her work such as black plastic combs-- combs which Sonya transforms into woven structures and social commentary on an industry built around having “good hair”.

And then-- she gifts Abraham Lincoln with better hair, building him a bigger and bigger Afro on five-dollar bills.

Sonya reminds us about our bodies – about the body – any body – as a site of embodied knowledge and site of production. For Sonya Clark, her thinking and her head of hair connect community-- today she wears the work of Kamala Bhagat. Other works remind us of the commodification of black bodies through slavery and the industries of cotton and sugar that continue to impact us today.

Sonya makes a space for craft to bring the world in – through her more recent work exploring sugar – into which she weaves the bolt of McHardy tartan made from hand-woven bagasse cloth – sugarcane fiber – that represents the Scottish line of Sonya Clark’s Jamaican family and the history of the world through a material practice.

Sonya Clark sounds the ancestors. When Macarthur awardee Regina Carter plays the United States National Anthem (“The Star-Spangled Banner”) and the Black American National Anthem (“Lift Every Voice and Sing”) using a bow strung with one of Sonya’s own dreadlocks, the powerful quiver is a reminder of the strength of what Sonya calls primordial fiber – hair – as a vehicle for storytelling and social commentary in itself.

She reveals the metaphoric possibilities of the simplest of gestures and elemental materials.

Sonya Clark stands in her piece Unravel the Confederate Flag, carefully unweaving the textile, thread by thread, separating out red, white, and blue into piles while talking with friends, colleagues, and strangers.

The power of the metaphor in this action and reversal from a structure to materials ready to be remade into something new speaks against a backdrop of this tumultuous election cycle and increased visibility of ongoing systematic assault against female and black bodies in a flawed social system could not prove any better that craft is relevant and endures.

Thanks to Sonya Clark, we can see craft in many places.

Please welcome Sonya Clark to the stage.

October 19, 2016

SAVANNAH GA

I write this first Critical Craft Forum blog post from gorgeous Savannah GA, which I am participating in the Textile Society of America Conference.

This first post connects the TSA Conference with the work of two artists included in Everything has been material for scissors to shape, currently on view at the Wing Luke Museum of Asian American Experience.

Surabhi Ghosh, Stephanie Syjuco and I are here in Savannah -- while Aram Han Sifuentes, the third artist in the exhibition, is participating this same weekend in the RaceCraft Symposium in CA.

More on the TSA Conference to follow -- in the meantime, here is a conversation Surabhi and I had during a lunch hosted by staff from the Wing Luke Museum of Asian American Experience back in May 2016 in Seattle WA. Our conversation covered a range of topics related to the exhibition and the context of its being shown in an ethnically-focused cultural institution, the types of work in the Museum's collection, and some of the cultural contexts behind the textiles on view that may not be immediately visible --- but are embedded in the material histories of the objects.

The conversation included Wing Luke staff: Roddy Ablao, Cassie Chinn, Rahul Gupta, and Michelle Kumata and Surabhi Ghosh and Namita Gupta Wiggers. Special thanks to the Wing Luke staff for a great conversation, for hosting the exhibition, and for ongoing programming during the exhibition's public run through April 2017.

CONVERSATION

Surabhi Ghosh: Growing up in the States, as all of us at this table know, we are constantly asked ‘Where are you from?” I was born and raised in the US, and find that now as an immigrant to Quebec that question has this whole other layer when I say, “I'm an American”. And then the next question follows: "No. No. Where are you really from? Where is your family from?" There's this sort of longer answer. My dad was an engineer so we would just go wherever the work was. So I was born in Texas, lived in California, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, Chicago, Oregon. But in a way it's also shorter because my family moved, I've moved all over the States.

Namita Wiggers: So In the States the answer is “Everywhere. . . .”

Surabhi: But then in Canada, I just say I'm from the States. Sometimes that actually ends the answer. The question of “where are you from” has been really complicated through this move.

Michelle Kumata: Do you still get the, "Really, where are you from?" I used to get that a lot here and growing up in the early '90s, mid early. But then I haven't got that question to me for a long time.

Surabhi: I've only been here in Seattle since Monday. But I've been really struck by how different it would be to grow up here in this city. I grew up mostly in Georgia, and the Southeast.. where people would often tell me where they thought... . They would tell me what I look like. "You look like you could be Mexican." Or whatever.

Namita: I think that's different if you're mixed. My son gets a lot of questions. My daughter is more obviously Indian, there's no question. But Calder could be Mexican, Italian, don't know what. He gets questioned all the time.

Michelle: Here in Seattle I get more the disappointed look from the Filipina aunties when they talk to me in Tagalog and then realize that I'm whole Chinese.

Namita: I’ve been clucked at many times. "Didn't your parents teach you your language?" I always want to say."Well, they did, because I was born and raised here. But there is guilt. . . .

Michelle: Is there any bias of Canadians about Americans that are... So what do they think?

Surabhi: Well, I'm in Quebec so cultural identity questions are different from the rest of Canada because of the specific colonial history. My favorite attitude is the one that's sort of makes fun of America. The Trump stuff happening has been … watching it from Canada has been interesting. It's so not real for them, whereas for as me and Rob it's been like, "Okay. We are applying for permanent residency; we are not going back to America. Whatever we need to do we are staying in Canada."

Cassie Chinn: So it that connected to your work in the show?

Surabhi: With the piece for this show the personal experience of being an immigrant is very much in the background. The work drew from sources related to storytelling and mythologies. The main story is the Draupadi story from the Mahabharata and makes a link between ideas of the infinite or how infinity plays out in different sort of sources..

The Canadian experience has been more in the background. I think it will go into what I do next. In Canada there's a whole line of arts funding called “research creation” where the process of art making is contextualized as research. As an artist, you don't necessarily know what the questions are until you make the work. This project has been very much like that. I feel like I still don't quite know what I made, what it means and what it's going to lead to. That's been really exciting about this piece.

It's the biggest thing I've ever made, it's taking me the longest amount of time. I've been working on it for nine months solid. I had two amazing assistants helped me with various stages of it. I had a research assistant named Emma Sise basically make the yarn hair, the blue hair, because I'm not a weaver. I described to her what I had in mind and then we worked our way through all these tests, and this was her solution. You can't see it but she actually wove it, so the yarns are all held together by weaving.

Namita: You could probably show visitors how that works. if kids were to hold up bunch of threads it would hang so differently.. There's a structure that makes it hang flat because it's woven part is up on the beam, right? When you just hold it like this, in a bunch, it's going to be all bunchy and rounded.

Rahul Gupta: So what it is about infinity in particular throughout the weaving?

Surabhi: It's an interest in impossibility that is making me work with the concept of infinity. I did another body of work last year about ways that people have tried to grasp the concept of infinity and understand it through material or mathematics, or through metaphor or story telling. But ultimately it's impossible to really understand what infinity is in physical reality. It has to be conceptual; it has to be theoretical or mathematical. So that's sort of an ongoing interest in infinity and the impossible.

And when Namita asked me to think about how... Actually whenever anyone asks me to think about what it is to be an Indian-American and how to understand that identity, I think it's impossible. I think it's an impossible thing to do, to really understand what leads to this part of who I am, who we are, what leads to this, what leads to that. And especially with Indian cultural identity being often written about as an impossible concept because India as a nation is so new and was split into three countries in the fallout of the colonial occupation. So it was the idea of impossibility that led me to return to the idea of infinity.

The two ways that I thought about story telling were Hinduism and learning about it through the "Amar Chitra Katha" comic books, and then also learning about identity and culture through my family. So both were filtered over to me in the States when family would come to visit or when I would read these comic books. I focused for this project on a kind of love-hate relationship I have with Indian culture.

So on the one hand there is something like the Draupadi story being so magical and miraculous, but also teaching me and lots of young Indian women about vulnerability, about needing men to protect you, about how beauty is defined by long hair, by fair skin or dark skin. Draupadi was very dark skinned. But I was taught that light skin was beautiful. So these sorts of ideas were filtered over, where I loved parts of it; I love the magic of it, the miracle of the infinite saree. But at the same time I was being taught things that really were at odds with learning about feminism growing up in the States.

So that's kind of what this piece is all about. It's about wanting to appreciate and critique culture at the same time, and then apply that to one's self and the challenges of doing that.

The other major visual source in the piece is related to Ananta and the Sea of Milk, which is also from Hinduism. The Sea of Milk is...it's infinite. It's the universe so it has no bounds. But the word "ananta" is actually defined as limitlessness. So it's not total infinity because it has a beginning, but no end. I really liked this when thinking about materializing concepts, because with material there's definitely that sense of a starting point or a source or something that begins. And the idea of something like a textile being infinite is impossible, but also metaphorically beautiful. I think it’s really relevant to thinking about materiality right now in terms of sources being limited,and resources being limited inside that.

The print is an ocean wave pattern from a watercolor painting from the 18th century. I speculate that a work like this would have been a source for, say, people writing and drawing much of the "Amar Chitra Katha" books. So it's sort of one step even further back in terms of representation of Hindu concepts - and it was a painted pattern of the Sea of Milk. In the Sea of Milk, there's a celestial thousand-headed serpent named Ananta who lives there and provides a resting place for the god Vishnu. And when the world ends Ananta will be the one who restarts the world. So Ananta can never be over.

I love that side of Hinduism - that side where it's about trying to understand impossibility and grasp concepts that are beyond human existence. I think Hinduism has that capability in a way that's super amazing and really inspiring, and definitely has impacted the way I think about the world. So that's the appreciation side of the work.

Michelle: And so how did the museum collection piece connect them?

Namita: That was my connection. The Committee [at the Wing Luke Museum] put forth two things that they wanted: contemporary textile artists, and they specifically wanted me to draw from the collections. So it gave me an opportunity to choose artists and objects that aren't necessarily just side-by-side but to create a place where that conjunction gives more meaning to each thing. Surabhi’s told me a lot about being of Gujerati and Bengali origin and the importance of Gandhi and khadi cloth to her. The making of khadi cloth as a political act was important in your personal history, right?

Surabhi: Yeah. And the piece is made from khadi. It's all khadi, and all khadi from India. It was always an important part of the stories my grandparents told me about the Independence movement.

Namita: That led me to the khadi piece in the collection as a way of juxtaposing that history, bringing it into the exhibition. That piece, the khadi piece that's in the collection, is so simple and understated. There's a place where it's been mended, and it's not mended in a really fancy way. It's very basic.

Surabhi: Humble.

Namita: Very humble. And the simplicity of that ties in beautifully with the simplicity of the line. Surabhi works very much in a minimalist way, where a line is never just a line with her work. Here the line and khadi have the weight of history and mythology, identity and commerce -- all of these things in a simple juxtaposition between the two.

Cassie: What was the process? Did the artist know what collections, objects you might be thinking about or was it more reflecting on their work and bringing that in?

Namita: It was never really “first this, then that.” When the opportunity came up, I immediately began researching artists. I called Surabhi and I said, "I have this space in the front. Your work needs room." Her work is simple but because of the way it occupies space it needs room to breath. We started talking, and had some conversations about the complexity of representing identity, and some of what Surabhi was talking about before. I know her work well, so I knew what sort of feel was going to come from it.

When she mentioned that she had a lot of khadi cloth she'd been saving,I went into the collection with that in mind, thinking about what in in the collection could be a partner. And it didn't necessarily have to be the khadi cloth. It could have been a very heavily ornate saree to balance out this simplicity with ornamentation. But that khadi bag was so perfect to get at this other part of history, the concrete history of Gandhiji and Swadeshi and Indian independence. It acts like a nice foil, so to speak.

It was a back and forth. I knew I wanted to bring Stephanie Syjuco’s work into the exhibition in when I saw that hallway space. As soon as I saw the hallway on the same day that I saw all of those baskets downstairs I began thinking about her Cargo Cult series. A lot of people look at those baskets and don't know why they're special that they're made by someone by hand or that they represent a very particular cultural history. Especially when most of our cultural connectivity comes through mass culture in the United States or comes from Pier 1 or Cost Plus. Even those are all based on really old weaving structures and weaving traditions.

Stephanie Syjuco, Cargo Cult Series, (left, Headbundle; right, Basketwoman), 2013-2016.

Stephanie Syjuco's work pulls the simplicity of the line from Surabhi’s work into the question of structure and systems.

While going through the collection, and I had a also built a list of 40 to 50 artists that I was considering, all of whom work through textiles and are Asian American. There are a lot out there.

While going through the collection archive online, I found all the oral histories of garment workers, and thought immediately of work by Aram Han Sifuentes, which I’d heard her talk about at College Art Association. It seemed like a marvelous way to bring out the individuals, specific people with names who are making and altering garments we wear in the US.

As you go through this space, you move from the mythological, the historical and this very big idea of space through the minimalism of the line through this question of identity as constructed through commercial products and mass culture, into the space where now there are named people. There are names associated with people who are laboring with textiles to make American identities. And it really, in a way, is an effort to subvert narratives and show that Asian-American labor has been the foundation of American identity. And so it gives that flip.

Stephanie Syjuco's Cargo Cult Series juxtaposed with baskets from the Wing Luke Collection

The final area includes textiles from Green Eileen. I could have just... it was hard choosing from the collection because there are unbelievably exquisite textiles down there. The reason that I pulled pieces from the collection is because I go to programs run by various textile groups. The kinds of things, for example, which Surabhi and I are involved in include a conference this fall for Textile Society of America. We're doing an exhibition and a panel. The workshops that happen in many of these textile groups are taught by people who are not from the culture that's being represented.

And I thought, you know, the Wing’s collection has this wonderful mixture of these very, very ornamental, special and everyday clothes. They're not like the MET’s collection. They're not the pieces that are the one of a kind for an emperor, for example. But they're exquisite in terms of workmanship. Wouldn't it be great if we could create a way to put responding to those textiles back into the hand of our visitors, so that we're not learning our textile history only from others? Instead, we could learn our history from looking and making ourselves. The reason it's located with Aram Han Sifuentes’ piece and the pieces from the archive is because this is the new labor space.The factories are gone, and what has replaced them is Green Eileen, a new model reaching towards sustainability through re-purposing. Thinking in terms of the site (International District) where the Wing Luke sits in the city, and in terms of commerce and labor. It's complicated.

Installation view, Aran Han Sifuentes, A Mend: A Collection of Scraps from Local Seamstresses and Tailors (Chicago), 2011-13 with videos of oral histories from If Tired Hands Could Talk: Stories of Asian Pacific American Garment Workers (2001); Interactive embroidery station with textiles supplied by Green Eileen and inspiration from textiles in the Wing Luke Collection.

Michelle: It's very dense, it's so layered. And I think it will be exciting as time goes on to see how are our tools go through, what the conversations are and how the visitors respond. It takes a while to figure that out. But that's why I love it, right? Where is a good starting point? It changes depending on who we bring through.

Namita: That's the power of a really good object and a really good artist. When you have this combination multiple stories can come out of it. One could argue that you can get multiple stories out of almost anything, to a degree. But what's happening in these three pieces is that you're getting personal and individual visions, perspectives, and leness that open up to bigger questions that are outside of yourself.

I think it will be really interesting. You could walk through and talk in a very formal way about the structures; all the pieces are simple. You could go through and talk about identity or about the history of textile manufacturing from the hand to the factory to recycling and re-purposing. There's lots of ways you can slice and dice it and none of them are wrong....

For me it's the first time that I was able to actually pull the postcolonial experience into an and get at the complications of living in a postcolonial world. I couldn't do that at the Museum of Contemporary Craft in the same way; it just wasn't the right space for it. The location here, this context of it an Asian-American-focused museum allows for the conversation to take different directions.

Cassie: Yeah, there's not as much context setting up because the context is already there. That's interesting.

Namita:It feels like you're telling the story from within while sometimes in other museums I feel like I have to justify the telling of a story because it's inserted into a broader narrative that didn't allow us to be present.

Michelle: It's a good way of describing it. We've talked to a fair number of folks time and time again that the shows that we have would be different in another location. And so it enables us to do our location in the museum and then the location in the neighborhood, to like you say, do things you couldn't do in another place, which I think is our asset.

Rahul: These are really great conversations. People can really open their eyes to see something so familiar but something . . . there's a deepness to it. People liked to dig into the surface reading up a lot of things. So I think this has a lot of weight for us at the Wing Luke.

NEXT UP: Podcast with Aram Han Sifuentes!

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •